Panic Blog

The Story of Playdate

By Christa

I recently posted the sixth episode of the Panic Podcast — a wide-ranging look into the creation of Playdate, our upcoming hand held video game system, based on over nine hours of conversation. It’s a really special listen. But I’m told not everybody listens to podcasts (outrageous), so I’ve made it a (long) blog post!

Listen or read, your choice. Either way, enjoy!

Ten years ago, the CEO and Head of Design at Teenage Engineering, Jesper Kouthoofd, got an email:

Hi Jesper,

We’re a small software company that makes Mac/iOS apps. For our 15th anniversary, I’ve been tinkering with an idea: find our 150 best customers, manufacture something incredibly special, and send it to them.

Here’s how an offhand idea to mark the fifteenth anniversary of a software company launched a decade-long saga of twists, turns, and mini-boss battles that led to a gaming console as surprising and unique as its creators.

First, There Were A Lot Of Ideas

Our story begins around 2011, though it’s hard to say exactly.

“It’s been going on for so long that I’m actually having trouble remembering how it all started,” says Panic co-founder Steven Frank.

While it’s maybe a little fuzzy now, at some point he and Panic’s other co-founder, Cabel Sasser, got to talking about the company’s fifteenth anniversary, which was coming up the following year. Panic had been making software applications for the Mac since 1997, and they wanted to create something to mark the occasion. Not software, but something tangible.

“We wanted to do something that felt kind of like a keepsake-y kind of thing, or just like a special thing that came out of nowhere. And the goal was to do something that we hadn’t done before. Not that we’re experts at, you know, what we do now. There’s always room to grow. But just to try to tackle something completely unknown and see what we can learn from it. And so that is why we ended up deciding to do hardware, of all things, for a software company,” says Cabel.

He and Steven soon realized that if they were going to make some kind of hardware device, it probably wouldn’t be finished in time for their fifteenth anniversary. So they set their sights on Panic’s twentieth anniversary, instead.

“You know, twenty years is a long time of doing the same thing. We enjoy what we do, obviously, or else we wouldn’t still be doing it twenty years later, but part of the reason I think why Panic is Panic, and one of the reasons why we never—so far—we haven’t sold the company or taken investments or stuff like that, is because we really appreciate the freedom of being able to do weird things. Adventures and strange side projects, and just having total creative freedom without having to be beholden to anyone, or make a lot of sense, or justify everything. We can do whatever we want to do. And I feel like as Panic has lasted longer and longer, I have begun to appreciate that that’s really unique and rare, especially talking to other people at different companies. That is a strange and special thing,” says Cabel.

So what better way to mark two decades of zany tangents and Panic rabbit-holes than by setting out to create some kind of novelty hardware keepsake… and then releasing it ten years later, as a quirky handheld gaming console with a robust SDK, a speaker dock, and two dozen surprise games from a variety of indie developers?

But let’s back up. The earliest ideas for this commemorative hardware project actually had nothing to do with games.

According to Cabel, “We talked about a lot of things in the beginning. I think one of my first ideas was a clock. Just a cool clock, and had all sorts of bonkers ideas like… God, had an idea for something that could maybe be made out of porcelain and the case itself could ring or chime. All sorts of unique ideas on clocks.”

So, yeah, we could’ve just made a cool clock. Happy anniversary! But, you know, Panic being Panic, and Cabel being Cabel…

“As I was researching displays, I came across this Sharp Memory LCD display. Actually, I’m not sure whether the display informed the idea of the device or vice versa.”

Steven thinks it began with the display.

“As best as I can remember, it was Cabel finding the screen, which is called a Memory LCD screen. And it has kind of the reflectivity of e-ink, but it’s not e-ink, it’s like an LCD,” he says.

“It’s not quite like e-ink. An e-ink screen, you have this big refresh rate thing that happens every time you update it, but it’s still kind of has this feeling of old LCD games, like a Game & Watch,” says Cabel.

A Game & Watch, for you vibrant young people who may be unaware, was a handheld gaming console made and sold by Nintendo in the 1980s. It came with a single game and also acted as an LCD clock. You could buy different Game & Watch devices with different games on them (but no matter which ones you had, your brother was always playing the “good” one on the family road trip).

“Those were segmented LCD displays,” Cabel says. “So you would define the art in advance and turn on and off different pieces of the art, but the resolution of the screen was so fine that it seemed like it could look like one of those, and the very, very original idea was what if we made a device that played a Game & Watch game, but then…”

“…but then somebody had what was maybe a bad idea where we thought, ‘Okay, well, what if something surprising happened?’” says Playdate Project Manager Greg Maletic. “What if after you got this game, a week later, it…”

“…could switch!” says Cabel. “One day you’re playing ‘Ball,’ and then, all of a sudden, you know, a week later, the screen could switch and look like something else? And it’d be cool if that was a surprise for people, where they thought they were getting just a standard segmented LCD Game & Watch game, and then a week later, it turns into something else.

The idea just morphed and grew over time. It was like: We all kind of like games. We want to make something hardware. We want it to feel special. We want it to be not like anything else. We want it to really confuse people, but also really make people happy. All of these things sort of came together.”

Where To Even Start?

The idea for a fifteenth anniversary keepsake clock had evolved into a twentieth anniversary Game & Watch style console that would, every so often, surprise and delight its owner with a brand-new game. The hard part now was how to go about building this thing. Where to even start?

According to Cabel, “There is a sort of pivotal moment earlier in the project where we went…”

“…to a company that does industrial design, and specifically for kind of one-off things like this,” finishes Designer Neven Mrgan, who was also at that meeting.

“And they were like a big local industrial design firm,” adds Cabel. “Like they, you know, design all these huge things and store interiors and physical products and the whole nine yards. And that meeting was really interesting.”

Neven is less diplomatic.

“They sort of blew us off as like, ‘you have no idea what you’re talking about. You’re never going to make a thing.’”

“We showed up, and like even the lead guy at the company was there, which is really kind of him,” says Cabel. “I think he thought we were going to be talking about smart watches, which is why he showed up, and so it’s him and an electrical engineer that they brought in that they consult with, and a couple of other people. And we sort of explain this idea of a gaming device and it changes and it does all this stuff, and they pretty much spent the entire meeting telling us not to do it, that it would be prohibitively expensive. You know, we’d be five million dollars in before we even had a prototype and the resources required will be massive. We’d need a huge team and somebody in the meeting is like, ‘Why would anyone even want this?’ And it was extremely demoralizing. It was one of the only times where I felt like this weird Steve Jobs part of my brain want to just like get up and leave in the middle of the meeting, which I’ve never done in my entire life. Of course, I didn’t, because I’m not that person, but it was just brutal. Now, I understand what they’re trying to say, because what we’re doing is crazy, I get it. You know, it’s like how people come to us and they’re like, ‘Hey, I have an idea for an app!’ and you have to be like ‘Ah, that’s a great idea, but there’s a lot of things to consider. It’s really hard and chances of success are really slim.’ We were those people saying, ‘hey, I think we have an idea for a hardware project,’ and they were the ones trying to be like, ‘you know, uhh, you guys gotta understand…’ but I think what they didn’t understand about us is, like, we’re trying to learn. Even if it ends up as a failure—which it still could!—what we’re trying to get out of the process is doing something new, and learning something. So that meeting ended horribly. I would quantify it as complete disaster.”

The meeting may have been a disaster, but Neven thinks it made Cabel even more determined to see the project through. Right afterward, Cabel reached out to Teenage Engineering.

Cabel really admired Teenage Engineering’s industrial design, especially of their OP-1 synthesizer. He knew someone at the company, so he reached out via email.

“I was just like ‘Hey, we have this crazy idea for this game system,’ and all this other stuff… and we exchanged, you know, a couple emails. And the first question they had was, ‘That sounds amazing, and can we make a game for it, too?’ I was like, ‘Oh, God!’ It felt so good. I was like, they’re people that understand it.”

And pretty soon, Cabel and Jesper got together to talk about it in person.

“I remember we had like a drink at Disneyland one time,” says Jesper. (Yeah, of course!) “And then I went to Asheville for the Moogfest, and met with Cabel and his team, and they showed me the first, like, prototype of the Playdate. It was basically just a circuit board.”

“We really only had one guy developing the initial prototype of the board, which is Dave, simply because he was the only one with really any electronics experience,” says Steven.

“He is the one that attached the screen to a printed circuit board and got the software working and actually brought a game up for the first time on a prototype Playdate, which still blows my mind,” says Greg. “I don’t know how he ever got that working.”

“So it all started with that circuit board that Panic showed me in Asheville, and I felt it could be a little bit smaller,” says Jesper. “I think it was like one and a half of the size that it is today. So it was a little bit higher, more or less like the classic Gameboy. You know, we all grew up with Nintendo and, and especially for me, the most inspiring memory I have is from the Game & Watch series. I think I was in the fourth or fifth grade when they launched the Game & Watch. I was blown away by the style of everything, the level of detail, the time that they had spent on, you know, like the small illustrations on this, this little game device.”

Panic decided on the code name “Asheville” for their Game-and-Watch-inspired device, in honor of that meeting in Asheville, North Carolina, where they first showed the prototype to Jesper at Moogfest, an electronic music and technology festival named in honor of synthesizer pioneer Robert Moog. (They also had some good barbecue on that trip, but I guess “Asheville” sounded better as a code name than “pulled pork.”)

The “Game & Watch” Concept Levels Up

The original Asheville concept was for a device that pretty faithfully recreated Game & Watch-style games, which are composed of LCD segments, which Neven explains are, “…kind of like an old-school clock, where it just has shapes that it can turn on or off. It doesn’t really have pixels all over the screen. That’s not how our screen works, but we thought, well, maybe it’ll look and work like that. And we played with that idea for awhile.”

But it turned out that the Game & Watch aesthetic only took them so far when it came to making games that were actually fun to play.

“I think I remember coming into the office on a Monday and being like, ‘There’s a problem, and that is that Game & Watch games are not very fun,’” says Cabel. “Because it’s true! Those games are great, but for like an hour. Maybe half an hour. You know, in 1982, they were incredible, but they’re just not super fun for very long periods of time. So then that was when we fully crossed the threshold into ‘I think it should be real games.’ And it’s kind of interesting to think about that, because clearly we were thinking in terms of scope, and cautiously, right? Like, we can’t make a whole game system. Maybe we just make simple Game & Watch games, even back to we maybe we just start with a clock, because that’s, like, an easy thing. Every step sort of just… the natural forces pushed us towards something more complicated but something that was better, and so once we decided, yes, it should be a real, real system that plays real games, then that sort of unlocked all sorts of other stuff.”

“That kind of opened up this huge box of, well, how do we get all these games in there? How do we make this platform that can support all these games?” says Greg. “It went from a very hard project to an incredibly hard project at that point.”

Difficult as it might be, they set out to make this thing real, with some help from their new friends at Teenage Engineering.

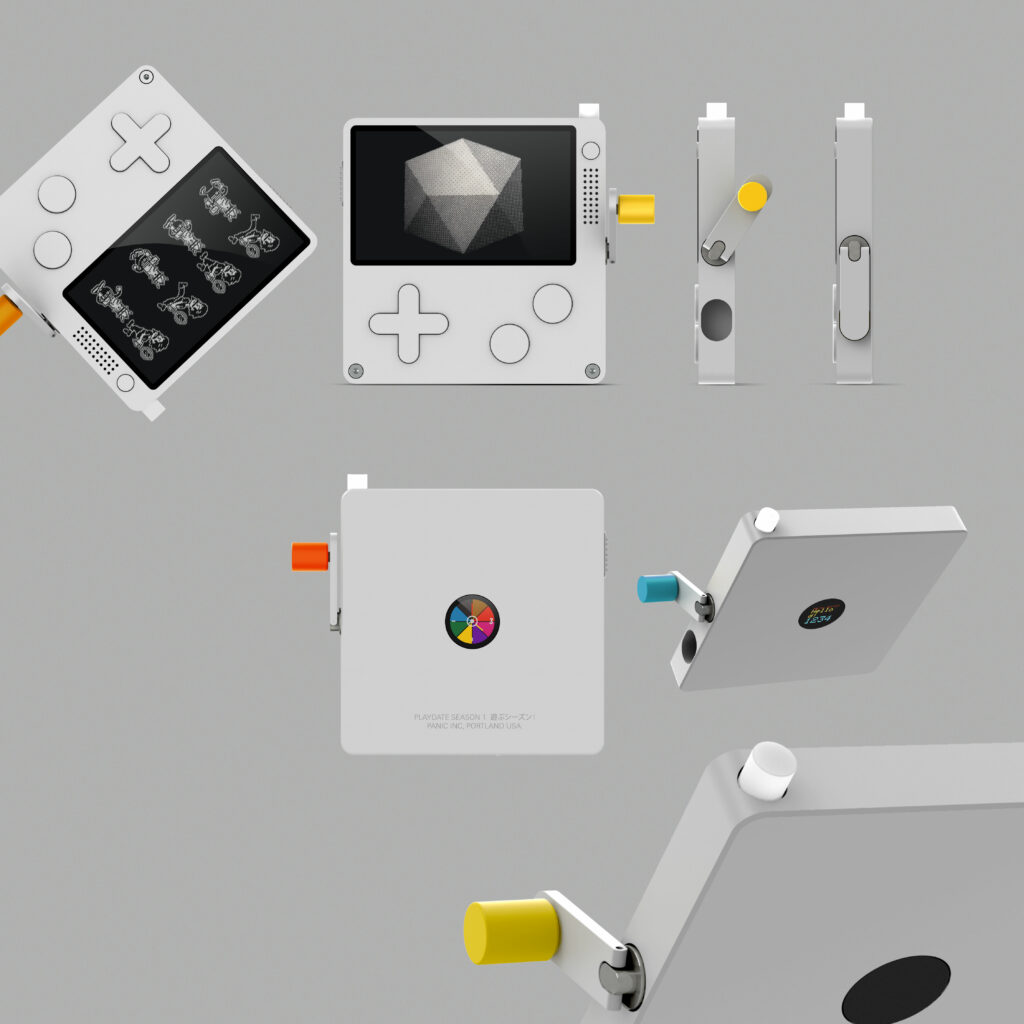

“They really loved the challenge,” says Neven. “And so they started suggesting some different inputs on it, you know, like, okay, there’s a d-pad, and there’s like some sort of action button things. Sure. Then they were like, what if there’s a crank for radial input, what if there’s some sort of touch surface on the back, or on the side? What if there’s a pinball-style spring that you can pull and release? And they sent back a bunch of these ideas and all of them looked cool.”

There was even one version of Playdate with a little circular display on the back, so you could flip it over and see some other part of a game, or access some other controls.

“The design process is for me, you just start with a lot of ideas,” says Jesper. “So I 3D-printed a lot of different form factors, different proportions, tried different colors, and layout of the buttons, you know. We both wanted to keep it very, very simple, but still, a little bit of our own identity in there. Why reinvent the wheel, when it comes to gaming, you know? It’s very effective, but usually when I design stuff, I really like to add one, at least one thing that makes it unique.”

“Famously, Jesper, the Teenage Engineering designer, said that he wanted to free us all of our ‘touch screen psychosis,’” says Neven.

“Everything we do is to create kind of like an alternative to, to the, what did I say? Touch-screen psychosis. To us, it’s very unsatisfying to use a touch device. I get it, and I think it’s a great interface for creating a lot of different applications without, you know, having hundreds of buttons and knobs and stuff. So it’s very effective for like a smartphone, but for a gaming device… A gaming device to me is almost the same as a musical instrument. It’s about zero latency, muscle memory, and you need to feel that you are in instant control of everything that happens. And that tactility, however you solve it, if it’s like pressing a button or turning a knob or a crank, it’s very important for the whole experience and the joy of being, you know, like in control and using your hands.”

“Eventually it came time to sort of decide what this thing is and what it isn’t. It couldn’t really have, you know, like 15 different inputs. So we all responded to the crank idea the strongest. So it was going to be the crank, d-pad, two buttons and then, you know, some housekeeping buttons, like, you know, power and menu, and it landed there,” says Neven.

So, it was decided: Asheville, which they were now calling “Playdate” internally, would be a delightful little handheld gaming console, with a high-contrast black and white screen, and a crank. And every so often, it would surprise you with a brand-new mystery game to play.

“The next step of engineering the whole device, taking all the ideas and see how we can solve them. And I’m also really happy that we could solve that the crank could fold in. So when you don’t need it, it’s not there. I really like how that came out,” says Jesper.

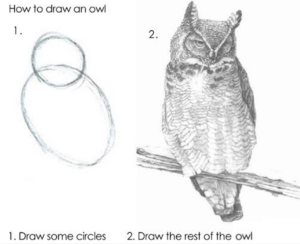

With the industrial design — that is, Playdate’s overall form — mostly in place, it was kind of like that meme about drawing an owl in two steps: First, you draw two overlapping circles. Then, you draw the rest of the owl. Panic had drawn some nice-looking circles. Now, it was time to make the rest of the owl. Trouble was, Panic was still essentially a software company.

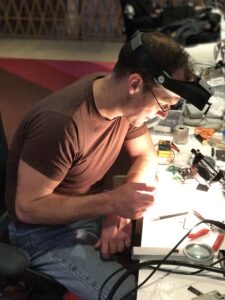

“You know, we don’t have an entire hardware team,” says Steven. “We have Dave.”

“Dave Hayden is the one that kinda got us going at the beginning, because he knows quite a lot about hardware,” adds Greg.

“It’s been quite a while, but it was just me on the project for the first few years. I’m Dave Hayden. I’m an engineer… yeah, I guess I’m a ‘real’ engineer now. I used to call myself a programmer. I was basically given free rein for a couple of years to just play around and learn and educate myself, which was amazing. Of course, then I had to actually produce actual results.”

Which he did! And Panic hired some more people to help out, eventually, including Stefan Burstrom, a seasoned electrical engineering consultant who, when he’s not busy skydiving, helps out on some of the electrical engineering for Playdate.

“He took my prototype schematics, fleshed them out, figured out all the power stuff that I didn’t know anything about, and then did the PCB [printed circuit board] layout,” says Dave. “I think the big mistake was that we had a working prototype in just a few months, and we thought, ‘Oh, this will be easy. This will be great!’”

Well, it has been great, but it has definitely not been easy.

Hardware is Hard

“Hardware is hard. Maybe that’s why they call it that,” jokes Steven.

“The problem with hardware is, you know, it’s like physics and stuff,” says Cabel. “It’s not like ‘let’s just throw open the debugger.’ You know, with software, if you have a reproducible test case, you can fix your bug. Like, that’s usually all you need. If you can get it to reproduce, we’re good to go. With hardware, you can get it to reproduce on a single unit, and it may not happen on any of the other units.”

Steven agrees. “Having always worked in software for twenty years, if something goes wrong, you can always do a patch or you can tell people, ‘Oh, you can fix this yourself by going and deleting this file or, you know, making this change.’ But hardware is, you know, hardware. It gets made in a factory and then it gets sent out to people and you no longer have any control over it. And that’s scary. It’s the first time for us. And we’re trying very hard to do it right.”

“The surprises that have popped up have just been things I never would have imagined could be problems,” says Cabel. “There’s a lot of those that I just didn’t know, and that just comes through experience. Like, we all know about them now, and had we seasoned hardware people on the team, then probably they would have been like, ‘Hey, watch out for X, Y, or Z.’ But definitely a lot of things can go wrong that I would not have expected could go wrong, and thinking about the clock chip and thinking just some of the esoteric… you know, like even the amount of effort and work we’ve put into making the d-pad and the buttons feel good. That’s like a single-bullet item on a list of goals, right? Like, ‘d-pad should feel good.’ It’s like, okay. What does that mean? There are a million answers to that question and sub-questions to that question, depending on how thick you want the case to be and how the flex board needs to sit inside the case. And it’s like the tiniest of things that you think are automatic are definitely not automatic. Way more so than I think for software, although software has the same problem. Like, okay, we need a button that logs the user into the server. Well, there’s, you know, a ton of ways that you can do that, but they’re very easy to iterate and try. I guess that’s the difference. With software, we can open up Photoshop and try 50 different approaches in, you know, half an hour. With hardware, if you’re thinking about the way the d-pad feels that’s the only way you can solve that, is to try to build things, and, you know, 3D-print things and laser cut things. And that is just like a totally different universe of complexity. On the other hand, it’s super rewarding, because you’re holding things and touching things and feeling things, and it’s like a physical manifestation of your work, as opposed to just sort of this ethereal thing that people download. So, you know, you win some, you lose some, but it’s hard.”

“We had some idea of how hard it would be to actually make hardware, but the number of little details is surprising,” Steven admits.

Enter a different Steven, who declares that, “Hardware is hard. But it’s not impossible.” This Steven, Steven Nersesian, has worked on Playdate since 2016, along with his wife, Jessica Nersesian, through their manufacturing consulting firm Metric Designworks.

Greg Maletic says Panic found Steven Nersesian through Teenage Engineering.

“They recommended him as somebody who could help us navigate the really complicated process of actually building Playdate. And he is a consultant, and he has done this many, many times before, with various companies. And he has been just invaluable to us. He found us the manufacturer we work with, S&O, based out of Malaysia. He’s done many projects with them in the past. And he’s helped us figure out how to get the parts for Playdate, how to design the custom parts for Playdate. He’s done a lot of the mechanical engineering for Playdate as well. I mean, it’s not an exaggeration to say that Playdate probably wouldn’t exist without him.”

“I’m kind of the overall coordinator between all the different disciplines that go into making a hardware product. I was an individual contributor on the mechanical design. Jessica was an individual contributor on the quality control level. I work with the electrical engineers and the firmware designers and the manufacturers and the executives at Panic to kind of refine the specifications,” says Steven, whom I’ll call “Steven N.” from now on, to distinguish him from Steven Frank, because despite recognizing the practicality of the standard journalistic practice of referring to people by their last names in stories like this, I prefer to use first names, because it’s friendlier.

“I’ve worked extensively with Teenage Engineering in the past, and, once they had finished the industrial design and kind of initial mechanical engineering concept, they advised that Metric should get involved and kind of take it through to the finish line,” says Steven N. “We were able to focus on it and really be hands-on with Panic to guide them through the process.”

And it was a complicated process. Playdate’s hardware and software were developed in tandem, with each side relying on the development of the other.

“The most challenging part of this project was that everything was custom, not just physically, but also inside,” says Steven N. “I mean, the software, the operating system, the firmware, everything to make the games possible beyond the physical product, required so much customization and iteration that, we couldn’t go as fast as we wanted to on the physical side, because we needed the software to catch up. And then once we got the software and loaded it on and we found challenges, we had to then again, physically iterate and electrically iterate. And so they were being done in parallel, but once everything converged and we were able to test everything together, well then there were changes that had to be made. And so, that just made the process take longer. One thing gated the other, and we had to just let that happen.”

Software is Also Hard

Despite the focus on Playdate being a hardware project and the difficulty inherent to that, there are a lot of software and firmware components that all have to align, too — not only with the device itself, but also with each other.

So, at the top level are the games that developers make to run on Playdate. Then there’s the operating system, on which the games run, and that manages the whole device, and the firmware that’s kind of below that, interfacing directly with the different hardware components. Then, adjacent to the on-device software and firmware, there’s a software development kit (or SDK) that game developers use to write their code, and Playdate emulators for Mac and PC, where game developers can run, test, and debug that code. And then there’s the software that runs on completely separate devices, on the actual Playdate assembly line — devices that run diagnostic tests at different points of production.

James Moore is the developer responsible for building the software that runs on the factory assembly line.

“James Moore has done an incredible job working on our QA hardware and software that makes sure every Playdate behaves the way it’s supposed to,” says Greg. “That was a big learning curve, because we’ve never done hardware QA before. We know a lot about software QA at Panic, but doing it on hardware is a really different proposition. And so we have all these different stations that are built up there that test a different aspect of Playdate as it comes around and comes down the manufacturing line. And James has just done a great job building that software from essentially ground zero.”

“The factory software is pretty different, in that I have to interface with a lot of pieces of test equipment and they, by and large, all speak a text-based protocol over a serial board, which goes back decades as far as computer interfaces go,” says James. “And so it was kind of fun to resurrect my knowledge from the ‘90s of talking to robots over serial ports and doing lots of text-based message processing. It’s pretty different from the kinds of things we do today with server and client communication over JSON, or what have you. Each one of these pieces of test equipment has its own way of telling you what it’s seeing or what values it’s wanting you to know about. So they’re all very unique and special. This was also quite a bit different from what I do normally at Panic, in that everything was running on Raspberry Pis, which introduces some constraints on processing power. And some of our tests are very processor-intensive. Working on an assembly line building a device like this is an exercise in Murphy’s Law like I have never seen before. Absolutely everything that can go wrong, will go wrong. The first trip we took to Malaysia, there were multi-day-long stretches of just knocking down a bug and running right into the next one, just all day long. And this was all working perfectly well in the office, but once you get there, all kinds of variables are introduced. An assembly line is a living beast, and you can’t really replicate that in the office.”

Dakota Ward worked on electrical engineering and on some of the assembly line software as well.

“What I’ve learned is that there’s going to be tiny variations in every single unit. And then if your software doesn’t account for that, it’s going to fail. It’s one thing to write software in an office in Portland, and then it’s another thing to have 300 units cruise through that software in Malaysia, and to see all the errors in all the corner cases that crop up and then to have to adjust to that. It really took us going over there and being there physically, seeing the process and seeing what the workers do, to gain an understanding of that,” says Dakota.

“Even if you have all the same test jigs, you’re not going to have ten people standing around all working with them at the same time, at different places of assembly,” says James. “And at the same time that I’m trying to fix bugs in the test code, Dave may be making changes to the firmware. And so, he might fix a firmware bug to address something that I’m seeing, and there might be some unintended consequence from that that could cause a failure at some other place in the assembly line.”

Dave is nonchalant about it. “Yeah, it’s Mark’s problem, now.”

Well, not entirely. But Panic did hire Marc Jessome to help with Playdate’s firmware in 2019.

“Marc is one of our senior firmware engineers and he comes to us after having worked on both the Pebble watch and the Fitbit, two actual products that really shipped. He’s actually shipped hardware projects before. We have not. So he’s one of the few people here at Panic that’s actually done this before, and that has been incredibly valuable. He got himself up to speed really quickly. And he works on things like making our WiFi faster, making our power consumption lower, making our downloads faster. Just a lot of things that are kind of in the plumbing. But really, really important plumbing that we need to have working, you know, reliably and fast. And so that’s been a huge, huge help,” says Greg.

“I’ve really enjoyed the fact that we’re a small team,” says Marc. “It means that I get to touch and work on absolutely every part of our firmware. Anything that needs to be fixed, I know that I can just look into, and it’s not worth, you know, handing off. When I first came onto the team, I was invited down to Austin to go spend a week getting to know Dave and sort of working down there, which was really nice. We had a good week of sort of deep-diving into how things work and discussing, you know, plans and what we want to do, sort of to kickoff time working on Playdate. It was super valuable, and great to spend time with Dave in person, as well.”

Absolutely! Dave knows all the good barbecue places.

“He took me to a great place. I can’t remember the name of it. But like a little trailer off on the side of a highway, and it was absolutely phenomenal. It’s everything that I’d heard about Texas barbecue,” says Marc.

Mmm, barbecue. But, back to firmware!

“So developing firmware is this sort of marriage of software and hardware,” Marc explains. “So what I do is the operating system that allows for games to run on the device, as well as allowing for games to interact with the hardware itself. So the Playdate has buttons that a user can press and the game needs to know when these are pressed, just as an example. Making hardware interactions available to the software that’s running on the device.”

“We know exactly how everything’s working from the ground up, whereas something like a modern desktop OS, it’s, you know, things don’t work and you don’t know why. And it’s like, good luck with that,” says Dave. “So I guess it’s kind of good and bad that we always know that we can eventually figure out what the problem is. You know, at the very bottom level, you can write the code at the very bottom of the stack. That’s really fun, being able to get down really deep into the guts of the thing.”

“Reliable firmware updates has been a pretty big challenge on the device,” says Marc. “It requires a lot of things to work together in harmony. You have WiFi, our web service that’s serving these updates to us, as well as, you know, storage on the device. And we need to make sure that all the components are in place in order to just successfully update and not brick the device. We don’t want to share bad firmware that ends up breaking hundreds or thousands of devices. I want to ensure that people are having a good time, but also, you know, we’re not causing this great device that they have to just be completely unusable. It’s a challenge, both in the sort of stress as well as in the technical and fun aspects as well.”

“It’s pretty, pretty thrilling,” says Dave. “I am just blown away that this weird dream we had suddenly became like… here we are on the other side of the world in a factory making it happen.”

Many, Many, Many Iterations

“It’s an iterative process,” says Steven N. “You start with your first prototype, ok, we’ve proved the concept. We can do the thing. Then we make something in roughly the form that it’s going to be. And then we all sit down and evaluate if we all like what’s going on, or what criticisms we have, we move to the next stage. With the Playdate project, there were many, many, many iterations just to get it to the point where everyone was pleased with what we had in our hands.”

It was, at times, a frustrating process. Each iteration of Playdate seemed to bring up new problems to solve. Greg remembers one trip to the factory in October, 2018 that was, at first, a little demoralizing.

“We got there and the units that had been produced for us, which were sort of test models, they both looked bad and the buttons didn’t work, and it was kind of a disaster. And we’d had previous units that worked great. And so I was like, ‘How did this happen?’ And it felt like we had taken about a nine-month step backwards. That said, when we started, you know, working at the problems, figuring out what was wrong, we figured out all these problems and we solved them. But it was at that point of despair when I kind of realized: you know what, I’m not going to be upset about this. I’m just going to take these problems as they come, and just accept that problems are part of the process, and just go with it, because hardware is tricky.”

And so the iterations continued slowly and steadily, to avoid the nightmare scenario of a bug or an issue — and not just in a few test units, but in thousands of finished devices.

“You don’t want to build thousands and have to fix it in thousands, right? So it’s about doing control runs,” says Steven N. “So it’s being very, very deliberate and disciplined about making ten, checking those ten. There’s a problem. Let’s fix that problem. Keep doing that until the ten are perfect.”

“And then there’s another ten and there’s a different problem. And then you have to fix that problem,” says Jessica Nersesian, the half of the Metric Designworks duo who handles hardware QA.

“And then increasing that quantity to twenty-five, do that for a few weeks,” continues Steven N. “And at each of those stages, being onsite was invaluable. To be able to be there and on the spot to be able to approve and advise and say, ‘yep, let’s go to the next stage. Let’s now try to build 50 and see how that goes.’ And as it scaled, we were able to help them refine their process and build confidence that they were doing the right thing.”

“It’s not something that can be done remotely,” says Jessica. “If they send us pictures of something and say, ‘well, do you accept it?’ I can’t necessarily see it in the picture. I need to be onsite and actually inspecting, and that helps calibrate for them, what we find to be the level of quality that we’re looking for, because they know that I’ll see it and they won’t let it through.”

Jessica has a wide-ranging job that focuses on quality assurance, she explains, “…through the whole process, both in connecting with what’s coming from the vendors, and then also, supporting each of the different operators in calibrating with what the standards are that Panic’s expecting to see, and then developing the QA process and training the quality assurance staff at the factory. And then I also help with setting up the line and other things, as needed. And within our partnership, I also try and focus on sustainability and research ways of getting a project ready for end of life. I actually come from kitchens. I used to set up lines for creating huge meals for a thousand people. So it’s very similar to setting up a factory line. In both instances, you’re taking components and then having to have everybody with the same high level of detail and focus.”

“Every single part that the constitutes to Playdate is custom,” says Steven N.

“So even something as simple as a screw,” continues Jessica, “you can’t just go onto a site, that we normally could, to say, ‘Okay, I just want that screw.’ Everything is being made from scratch.”

“The components are packed in quite tightly. And so even for the screw, we needed the head of the screw to be a thinner dimension than what we could find off the shelf, we needed it not to be quite as long because then it would go and hit the LCD, right? So every single component is being made on a custom basis,” says Steven N.

“We receive components,” says Jessica. “Part of the factory reviews every single component and sees that it’s quality. Then it goes to the line, and then: imagine you’re doing a crazy puzzle that is incredibly hard to put together, and you’re doing it with fifteen other people. And so, each person does a small component of this and then passes it to the next, and anyone who’s not at full calibration of what our quality is will pass on something else. And we don’t want it to get all the way to the end of the line and have to scrap the unit. So it goes through multiple checks, both in firmware, and visual inspection. And then it goes on to quality assurance. So it’s getting checked for minutes at a time, not just whether or not the crank moves, but that’s a big one. But every gap, we measure. Every millimeter along the edges of the device, we check for the amount of dots, we check for scratches. And each iteration of the different builds, we would have new things come up where sometimes the crank would sag, and before it never did that, or we would have a gap at the screen and it would never do that before. And so it’s a lot of the group getting together and trying to figure out how to resolve a new issue.”

“There’s fifteen individual stations with templates and jigs that help things be aligned properly,” says Steven N. “The first one is checking the LCD to make sure the LCD lights up. The next one is gluing that LCD into the front housing. And that’s a different person, right, who’s manning that station, and whose job is to understand what is okay and what’s not okay. And so being there, we were able to work with each individual station and each individual person. And there are multiple people that run that station, depending what day it is. If one person’s sick, they need a backup, or… so it’s training all the individual people and sensitizing them for what we’re all looking for. So how do we make it as error-proof as possible?”

The answer? A little at a time.

Developing the Development Kit

While adjustments to the assembly line and quality assurance tests continued to be worked out at S&O in Malaysia, Panic was hard at work back in Portland on the operating system (or OS) and the software development kit (or SDK). Basically, all of the various infrastructure that game developers would need to actually write a game and put it on a Playdate.

It’s been a collaborative process with a lot of different folks at Panic, with contributions from Shaun Inman on a tool called Caps (a web-based tool for creating and editing Playdate fonts), and Will Cosgrove, who built the Playdate simulator for Windows that developers use to run, test, and debug their games if they use a PC, and firmware and low-level OS work from Marc Jessome. But a lot of the work on the operating system and SDK was done by Dave Hayden and Dan Messing.

“Dan Messing has done an incredible job on the operating system and on all the kind of user-facing apps, including the main launcher for Playdate,” says Greg.

Dan Messing is a software engineer at Panic.

“So I worked on a wide variety of things,” says Dan. “Everything from sort of the home screen to the Settings app, to a lot of different aspects of the SDK. So things like pathfinding and collision detection and some fun stuff like blurring [1-bit] images, and that’s actually a good example of collaboration, because I think I did the first implementation of blurring and dithering, and then Dave came along after and did a bunch of optimizations to it to make it faster on the hardware. A lot of it’s been stuff like that, where everybody touches something in one way or another. It definitely has evolved over time from the first sort of implementations where Dave figured out how to get a picture showing on the screen. I’d say it’s grown sort of in conjunction with the Season One games. So it was a good sort of feedback loop. As we were working on the Playdate OS, games were being developed for it. Either the Season One games, or just folks in the Playdate Developer Preview who had been working on games for awhile. So as people worked on games, it allowed us to develop the SDK sort of in a very focused way. People making the games, you know, asked us if there was a way to do something and we thought, ‘Oh, it would be good if we provided a way to do that, instead of making every game implement that thing on its own.’ One example would be the pathfinding algorithm. There was one game that needed it, and they were going to implement their own solution in Lua. But at the time I thought, ‘Oh, well, I’ll just do a C implementation because pathfinding is sort of a common thing for game developers to need. So, might as well build it into the firmware, make it faster for that developer, and available for all developers. And I think there were a lot of situations where things like that happened. When developing the SDK, we have to do a lot of API design for that.”

API stands for “application programming interface.” In our case, it means standard ways for your code to tell the Playdate system what to do, like that pathfinding algorithm Dan mentioned.

“And I think it was fortunate that I was so familiar with the Mac and iOS SDKs, like Cocoa and App Kit and everything, because I think they’re pretty nicely designed APIs. So that was good to sort of have that background of what works well and what doesn’t work well. So, I’ve been on the other side.”

So has Dave… and recently. He said his experience with working with the SDK for the Bluetooth chip that Playdate uses has been an example of what not to do when designing our own SDK.

“Bluetooth is kind of a many-headed Hydra sort of beast thingy,” says Dave. “There’s all these different layers to it and protocols and whatnot. And, the chip that we’re using on the Playdate… their code is not the most developer-friendly code I’ve ever used.”

Of course, Dave found something fun in the Bluetooth implementation, somewhere.

“Fun? Nothing. There’s absolutely no joy in it at all. I’m not kidding. It is almost the most soul-draining thing I’ve ever done. Working with the SDK is, oh God, it just kills… I mean, oh… Yeah. I could I could I could give you lots of complaints, but I don’t like to complain. Ha, right.”

Uhh, so… it was good to keep the Playdate game developer in mind when developing our own SDK. We didn’t want anyone to have a bad experience developing a game for Playdate! And like Playdate itself, the OS and the SDK get their own quality assurance process.

“Ashur Cabrera has been doing an incredible job on QA, getting these releases of our software development kit out in a timely fashion,” says Greg. “That’s been a huge deal, because we have developers that rely on this software. It has to work. We don’t want it to break any of the old software, any of the old games that are out there. It has to work every single time. And so, he’s done an incredible job, making sure that it’s reliable.”

SDK reliability is key, because every single Playdate is also a developer unit. The SDK is still in a limited preview now, but eventually it will be available for free for anyone who wants to use it to make a game for Playdate. No pressure, Dan!

“It’s interesting being on the side of making an SDK for people to use, and trying to think about it in a way that makes their life easier,” says Dan. “A lot of the stuff that I’m thinking about is how to make the people that are using the software have a good time, and coming up with ways to make it easy to use, and all that stuff is consistent.”

And speaking of consistency: every operating system has to have its own internally-consistent interface grammar.

The Look and Feel of Playdate

The design of things like system settings, menus, input fields, and buttons may not be the first thing that comes to mind when you think of a particular device, but that kind of base-level design not only gives different systems their own identity, it’s crucial to get right, so that users can quickly learn how to use the device and know what to expect with each interaction.

Neven designed the Playdate OS.

“We went through a bunch of different ideas,” he says.

Hey look, another iterative process!

“One thing we realized early on and that we felt strongly about is that this is not like a smartphone,” Neven says. “It is not going to have a persistent status bar that shows you your WiFi network strength and such, because those are not as important in a device that, you know, you don’t use for a million things a day, you use it to play games. So a big focus for me was that this is a device that gets you to playing the next game that you want to play, and kind of stays out of your way. Now, when I say it stays out of your way, that doesn’t mean that it’s dry and has no personality. You know, there are times when you have to use the OS, you have to connect to WiFi, you have to change something in Settings.You have to choose the game that you’re going to play or install. So we tried to make that part fun. One thing is we have that crank and so, it’s not so much that we use it a lot in the OS, but a lot of ideas around how the OS is designed were made so as to, kind of, speak to the crank.”

I want a shirt that says, “Speak to the Crank.”

“I try to avoid having grids of buttons and things that look touchable,” Neven continues. “I mean, you know on some level that the Playdate does not have a touchscreen, but still your lizard brain wants to touch it. So I try to instead have lists of things that scroll up and down. So the main launcher where you find, you know, all of your games, is this like linear list that you’re scrolling through of the games, and you can use the crank to scroll through it. Every game’s launcher art—you know, think of that as like the icon on your phone—can be animated. So when you’re on it, it can be animated. When you launch the app, there can be like an animation into the app and, you know, and the sound follows it. So, ideally each game’s personality is there when you’re about to launch that game, or when you’re going through the games, checking them out one by one. That is where I hope people spend 99% of their time on their Playdate, not changing their WiFi password. And that is where I like having each game provide its own stamp of personality.”

There are also some fantastic surprise animations in the OS that were created by a company called Chromosphere.

“So with the Playdate OS, there’s not a lot of it, if that makes sense,” says Neven. “The main things that you will see as you use it are that launcher, where you see all your games and launch them. You have the Settings app, which is kind of a bunch of, like, tables of text, where you change what kind of clock you want to see and you know, your WiFi network password, so the thing with the Settings app and the Menu is that they’re quite simple, and they don’t waste your time. That’s something that’s important to me, that when you’re trying to change your WiFi password, you are not being kind of sidetracked by a bunch of goofy animations, when you’re just trying to do this administrative task. That doesn’t mean that they have like no flavor whatsoever. For instance, when you launch the Settings app, it shows this little animation. You know, it goes from the launcher art to the app. That’s just because that launch takes some number of milliseconds to happen anyway, we might as well show you, you know, an animation, same thing with the Menu button. Dan Messing did this really nice little swipe of that menu when it happens. That kind of stuff does feel like personality, and like a little bit of a vibe to Playdate.”

Almost as important as the visual feedback you get from using the crank to scroll through games, are the system’s audio cues that provide user feedback for various inputs. Playdate’s interface is full of delightful clicks and beeps, thanks to sound design by Simon Panrucker, who, along with Cabel Sasser, also composed the Playdate theme. You can hear the full song here.

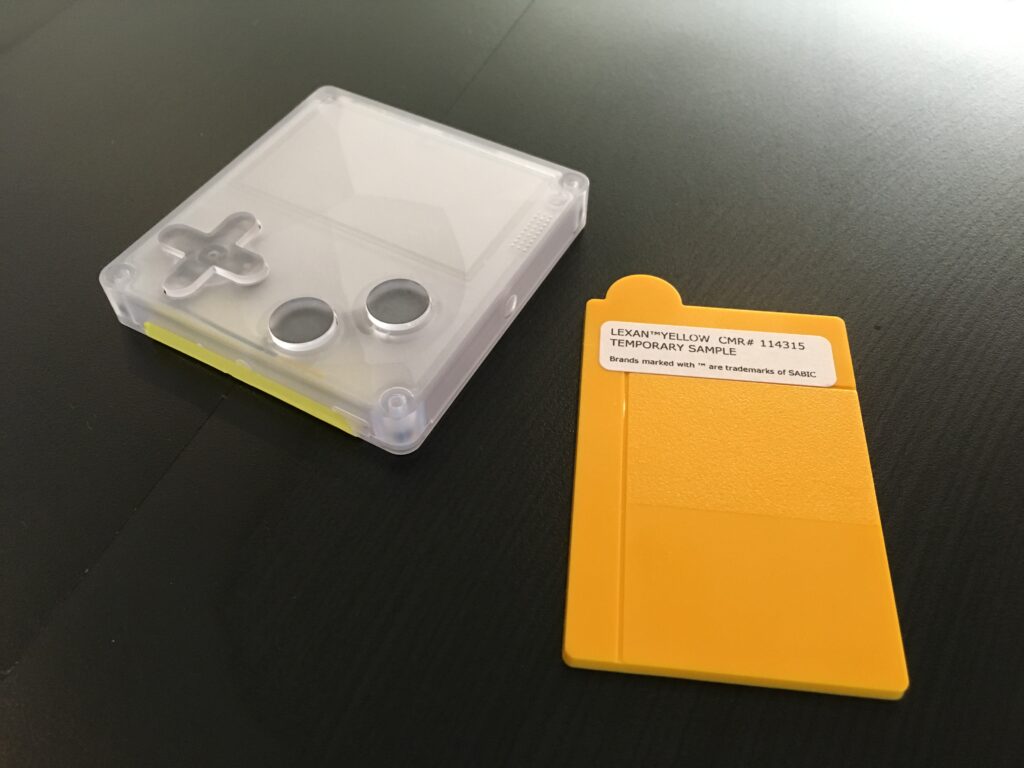

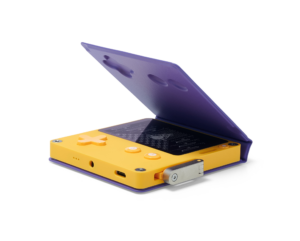

So, yes, the interface design is vital, but of course it’s just one aspect of the overall look and feel of Playdate, with its one-bit black and white screen, the curious crank that flips out from the side, and its cheery yellow plastic case.

Little. Yellow. Different

“You see a lot of yellow,” Jessica admits.

“Panic has a long history of liking the colors yellow and purple,” says Neven. “They were right there in the icon of Transmit, one of our oldest apps. And we’ve always liked them. I think the reason we like them is, one, they’re like fun, summery colors, you know, that make you feel a little bit flashy. They’re also colors that most companies out there are, like, too cowardly to use in their branding. People move towards like blue, or red, you know, rather than, you know, purple or yellow or orange. When it came time to start talking about the color of the actual Playdate, I think the thing that informed the decision the most was the fact that Cabel had on his desk a Famicom disk.”

The Famicom Disk System was an accessory for Nintendo’s family computer game system. It was only released in Japan, and used its own special floppy disk cartridges.

“And those were that like exact bright, warm yellow,” says Neven. “And it’s also square about the size of a Playdate. And it’s also made of plastic. And so just sort of like spotting this thing on his desk, it’s like, ‘oh my God, it needs to be that yellow.’”

“We’re really fond of an era of electronics, kind of in the 80s and in the early 90s, where things weren’t afraid to be colorful and kind of boxy and have weird proportions, or things being off-center,” says Cabel. “We kind of went from that era into, really, the iMac I guess ushered us into sort of a more refined version of that, which was everything is transparent plastic and, you know, fairly clean. And then it started to get cleaner and it started getting cleaner and then it’s like everything’s a rectangle that’s white, or you know, everything has rounded corners and is silver, and that seems to be where most things are today. So I think we are really looking back at— I mean, God, even the original Sport Walkman! That yellow Sport Walkman is so good. Sony really were sort of the masters of creating that kind of stuff, but I feel like that’s sort of the era and that’s what we wanted to be, was something that felt fun and cute and cool, and did not take itself too seriously. Because it’s weird how we went from the iMac, which most definitely didn’t take itself seriously. I mean it was like, you know candy purple and then there was the blue Dalmatian one or whatever and there was like, I mean, even, God, is there a computer that could be goofier than that sunflower hinged lamp iMac with that goofy rounded base and all that? You know, but it was cool and cute. That stuff’s just gone. But anyways, it’s a bummer because I kind of like it when things are goofy.”

“Even though we tried some other colors, just sort of, you know, as tests, we just kept coming right back to that yellow, because it’s bright,” says Neven. “There’s not necessarily a console or even like a piece of consumer electronics that is canonically yellow. You know, if they offer a bunch of colors, eventually they might offer yellow, but it’s not something they rush to as like their original color. So I just felt like we could own this yellow, and we could feel so proud and happy to make a thing that is known for being yellow.”

The box had to be yellow, too.

“When you are receive your Playdate, it’ll come in its cool yellow box, which I hope you think is cool enough to keep. If not, I totally understand,” says Neven. “But if you decide to keep it, it’s sort of the size and shape of a book, so it’ll fit nicely on your bookshelf. You can just jam it in between two books. We originally wanted to put on the side, on the spine, the number ‘one,’ as in like ‘Season One of Playdate,’ but then we thought that would be cruel because, you know, if there’s a two and a three, it’s forcing people who are in the collector mindset to collect them all. And, you know, we don’t need to give people any more stress in their lives.”

Yeah, no kidding. If you’ve listened this far, you’re probably understanding why this project has been such a massive undertaking for a fairly small software company—around twenty people when work on Playdate began, a little bigger now. We’ve gotten pretty deep into the story of Playdate without mentioning that microscopic elephant in the room: SARS-COV-2, the coronavirus that caused the global COVID-19 pandemic. You can probably see where I’m going with this.

Playdate in the Time of COVID

“Of all the things that we were mentally prepared for in trying to create our first hardware product… Yeah. Just like everybody on the planet, nobody could have foreseen what happened with COVID,” says Cabel. “Like all of the human beings that have gone through this and are continuing to go through this as we record this, you know, it was a one day at a time thing where all of a sudden it—you know, we’re like, ‘huh, this thing looks like it’s getting kind of serious. Hmm. Weird.’ I remember not understanding anything about it. I remember asking like, ‘wait, so am I…what’s wrong with going to the store?’ And like other people at Panic having to like, explain to me how a pandemic works. Feel kind of dumb in retrospect. Just with every passing day, things got a little bit more unusual and one day we’re like, ‘boy, I don’t think we should be going to the office anymore.’ Everybody grabbed their machines and, you know, we’re all just a hundred percent working from home remotely, and you know, there’s good and bad, but like, I think if you had told me that, in the final mile of creating this thing, you’re going to have to switch to working remotely, my instinct would have been, ‘that is a horrible idea and it will lead to absolute disaster.’ Clearly I am wrong. I would have been wrong, because it has not been that bad. I think we learned that we can do this, that we can be apart from each other and still creating something together and it’s not quite the same, but functionally, we just kept cranking and making things and working through the process. Then there’s the second part of it, which is the factory.”

“Our factory in Malaysia did shut down for just a brief period of time earlier this year, maybe two or three weeks, it actually wasn’t very long,” says Greg. “But the biggest issue for us was the travel restrictions that Malaysia put in place. Just as we were about to start ramping up production, they required us to get special permission in order to enter the country. And we thought we could do that, but it wasn’t that easy. And the other thing was they required a two-week quarantine. Once you arrived, you had to stay in a hotel once you got there. And that just made us traveling there that much harder. Fortunately, our manufacturing consultant, Steven — he and his wife Jessica bravely and heroically decided to volunteer for this duty. That helped us out just tremendously. We needed somebody there when manufacturing was starting up to watch over quality, watch over the production methods, make sure everything was going well. And having them there in person just made all the difference for us.”

“We basically had a surprise semester abroad,” laughs Jessica.

In fact, she and Steven N. ended up staying in Malaysia for five months—in the middle of the pandemic.

“So it took us six months just to get approval to come into the country, which—usually we just fly, get a landing visa, no problem. In the course of that six months, we were working with wonderful officials from the government, from the US side, from the Malaysia side, everyone working together to get us out there, but we’re flying fourteen hours, and we don’t know if we’re going to quarantine together. And we don’t know where we’re going to be, and we don’t know what the food is going to be. So we packed a huge suitcase with provisions and gin, and we arrived at the hotel and all the staff were in hazmat suits, and we were being carted around in these different cohorts. And finally we did, in fact, get to quarantine together in a small gray room run by the Malaysian government. But on the other side, we were finally able to get out to Penang, out to the factory, and there was a lot of movement control. We had to go to the police station regularly and get approval. We had roadblocks where we couldn’t pass between different areas, which was problematic for the whole process of vetting vendors, because there’s a vendor who’s supposed to make the screws and we can’t go and visit their factory and see what their quality is like. And so everything ended up being a bit elongated in that way. Restaurants were closed. Grocery stores were accessible, but we had to only stay within a certain area, or the police would stop us. So it made it a bit of an adventure.”

“It was pretty grueling. I mean, it’s 45 minutes each direction to the factory and back,” says Steven N.

“We were there somewhere between eight to twelve hours a day, depending on what the push was, and masks all day in the factory. We still weren’t vaccinated at that point, so we were nervous. The cases were better there than they were in the US at the time, but I don’t know, it was an adventure and we had no idea we were going to be there so long. Most trips when we go there are…we’re there a few weeks, maybe a month at the most. And then we come home and we unpack and we re-pack, and then we get situated to go out again. This time, we were there for five months.”

“It really is kind of a trickle-down issue where we couldn’t go to the supplier side in most cases, because they were in a different district and we couldn’t travel to that district,” says Steven N. “Or if we could, we couldn’t go in without a negative COVID test. And then there were so many things that layered up on top of that. Even them getting things from their suppliers. So they’re, you know, getting raw materials, getting steel, getting paint, getting plastic resin, those things even gotten elongated. So it just, anytime we’d had one of those iterations where we said, well, this isn’t quite right, let’s make a design change, instead of taking a week like it normally does, that might take three weeks. On the electrical components, I think by now everyone’s heard about the chip shortage. And those are standard chips. They’re being made and being supplied to many people around the world. That’s just one aspect of kind of, the supply chain. In that case, it still is an ongoing challenge. You know, every day it’s some new vendor that’s extending their delivery deadlines and wanting to increase costs.”

“It’s just made an already uncertain process — it’s added that much more uncertainty to it,” says Greg. “So parts of it did become really difficult to find this year. Any electronic part, strangely, is in short supply. It’s some of the obvious things like the screen and the CPU, but also things like the chip that controls the USB port, for example. They’re all difficult to come by now. All have lead times that stretch into the several, you know, six months, nine months sometimes. And so that’s been a real challenge. We have enough parts to build the first twenty- or thirty thousand Playdates. The tricky part is trying to build that twenty-thousand-and-first Playdate. That’s when we have to wait on some new parts to come in. And it would be easier if we had a clear forecast for how many Playdates to build, but we still have no idea how many customers out there want a Playdate. And so that’s made it really difficult to plan ahead, which is why the pre-orders are so important for us to figure out actually how many people want this. We did have to raise the price a little bit on Playdate, to make up for some of the cost increases that have taken place over the past year. Some of our parts have gone up by 20 or 30%, which is a pretty good increase. But also because of the part shortage, there’s sometimes an opportunity for us to get parts faster. If we offer more for them, say if a part is $3 and we can’t get it, we could say, ‘well, if we pay $4.50 for it, can we get them any sooner?’ And sometimes we can. So we wanted to both cover the cost increases, and make some room so we could pay for additional increases if it meant we would get parts sooner.”

And, this won’t affect Playdate pre-orders, but: the factory did end up having to close again recently, for most of July 2021.

“Our factory fully closed a couple of weeks ago, until the end of the month, which is a hundred percent the correct thing to do, but being so far away, you know, it’s hard,” says Cabel. “We want everybody there to be safe. I mean, God, for a second, we’re like, ‘can we help send vaccines to the factory?’ Like, you feel kind of powerless. I don’t want any of the incredible people that are building this product every day, to— certainly, making a Playdate is not worth being sick. And it’s hard to be so far removed from that situation and feel hopeless in being able to help them, but we know it’s a very good place to work and they definitely care about their workers. So I know they’re going to make the right decisions and look out for everybody’s wellbeing.”

A Human Endeavor

When you’re so far removed from factories and manufacturing, like most of us reading and writing this blog post are right now, it can be hard to remember that manufacturing is essentially a human process, and not very automated at all in most cases. There are no faceless robots assembling these Playdates. It’s a bunch of passionate, hardworking people at S&O.

“S&O stands for Sharp and Onkyo. It’s co-owned by both of those companies,” explains Greg. “S&O is great— just incredibly helpful, incredibly enthusiastic, and very motivated to make our project succeed, which is a wonderful feeling.”

“This is a factory that’s been open for decades, and most of the people who work there have been working there since they got out of school,” says Jessica. “So there’s this deep connection and a family sort of atmosphere. We have such a wonderful team and it is a human endeavor. It’s not just putting a widget in one end and having it squirt through a machine and then pop out all finished and ready to go. And we all have been working on this since 2016. It’s been an endeavor that the operators at the factory are invested in, as well. They’re excited. We were spending New Year’s Eve all together, getting the line in order and trying to get everything out and me shouting across to everyone: ‘OK, we have ten more! We have ten!’ And everyone excited and clapping. And all our time in Malaysia has helped us connect at an individual level, where I know Linda is the one at inspection, and Bala is the one on QA, and Vanni is the one at audio and everyone is working together, and that collaboration is wonderful.”

With a project as big and complicated as Playdate has become, and all of the setbacks from manufacturing issues and pandemic delays, it’s easy to find yourself asking, ‘Why are we doing this? This is hard.’

Greg is upbeat. “I think the biggest lesson I’ve learned is to not be discouraged by failure, because failure is really part of the process, especially with something this complicated. And the fact that we’re doing it for the very first time ever, we’re going to fail a lot of times while this is being developed. And it’s easy to get discouraged by that. And I definitely have been discouraged at some moments, but, you know, we’ve solved every problem we’ve hit so far, and I am hoping that we will continue to do so. I think we will.”

Definitely.

A Season of Games

Incredibly, through the upheaval of the pandemic, people have continued to make amazing games for Playdate. It’s been so cool to see Season One expand and change over time from the original concept—which was partly in response to the Netflix binge-watching culture that was emerging in the 2010s, where a new show would come out, but release all of its episodes at once.

“People could binge-watch the entire new season of whatever it was, like ‘Arrested Development’ at the time, or something, like in one day. And a lot of people would do that. And, I sort of did that,” says Neven.

“Maybe not in one day, but over two or three days with some of these shows. And then we realized that we talked about these shows for two days, and that was it. They just like evaporated from the cultural conscience. And so we thought that there is something cool about the sort of weekly water cooler effect of having stuff that is delivered weekly. And so we thought, well, what if we have a season of games? So you get a game a week, which gives you a pace. So you’re not just like quickly trying to play 20 games and then maybe like not really giving a chance to a game because there were 19 others.”

“I think there were a few things going on at once that led to sort of this idea,” says Cabel. “One, in the office, Neven and Greg had started doing this thing they called ‘Match Cut Movie Club,’ where you would show up to a movie theater for a movie or multiple movies, and you had no idea what the movie was going to be. You just had to trust that Neven and Greg have pretty good taste in movies, which they do. And the idea was that you roll in, you sit down and you just see where the screen takes you, that’s a very unusual concept in today’s modern times, where certainly with the arrival of the internet, nothing is a surprise anymore. I mean, every movie that comes out we’ve tracked for years, every video game, every inch of the development is revealed. We have a lot of information. So thinking about Match Cut Movie Club, I think it was probably part of the inspiration for Season One.”

Greg recalls yet another source of inspiration for the “weekly surprise game” idea: “We thought back to what video games were like, kind of pre-internet. And how you didn’t know what was coming out next week. It just, you would go to the store and there was just a huge surprise shelf full of stuff that you didn’t even know was going to be there. And that’s the kind of experience we wanted to recreate, where you didn’t know what was coming next. And it was just a, you know, series of endless surprises.”

“Even if not every game is a hit for them or not every game resonates with them, the feeling of ‘oh, there’s a new game today! I can’t wait to check it out.’ I just want people to have that feeling because it’s such a good feeling and I feel like as we go through life, it gets harder and harder to capture that feeling,” says Cabel.

“Initially we thought, well, maybe we’ll sell, you know, 10,000 Playdates,” says Greg. “We can pretty easily make all those, put them in a warehouse, ship them all out, get them to everybody. Everybody starts the season on the same day and plays the games and that all works great.”

“The further down the road we got with Playdate, the more we realized Season One is not really compatible in any way with how things are manufactured,” says Cabel. “In our naive, beginning mind, we thought, well, we’ll make X number of Playdates and we’ll just ship them all to everybody. And then everybody gets all the games at the same time, at once. And that’s not really… Hmm, I’m going to say, possible.”

“We think we might have more than 10,000 customers now,” says Greg. “We don’t know how many more, but it could be more, it could be a lot more. We can’t build and ship that many Playdates concurrently. It’s just not really feasible for us. So instead of having the model where everyone was playing the season at the same time, we switched to a model where the season starts at the moment you turn on your Playdate for the first time. Once that happens, you’ll get the first two games. And then every week after that, you’ll get two more games, for twelve weeks. And so everyone is on their own season schedule rather than on one coordinated, universal season schedule. It means that everybody has the same experience. Everybody has the experience of getting these games over time in the same order, same sequence and it’s just a more consistent and we hope more fun, approach for people who get their Playdates later in the year.”

Some people will get their Playdates at the same time, since they’ll be shipped in batches, but one cool way to experience the games of Season One might be to organize a sort of Playdate book club with your friends.

“We’re going to have a lot of really cool games, and it’s only natural that you’ll want to play them with your friends,” says Greg. “And so if you and your friends want to sync up and decide to hold off on a certain game until a certain date and then play them together, either live, you know, over zoom, or just talk about them after they’re done, I think that sounds like a great idea.”

“And the funny thing to me is that we thought it would be a struggle to get 10 games made for this,” says Neven. “So we started working on some of our own games and very cautiously approaching some people about making them. And now, you know, we sort of have the opposite problem, which is that so many people want to develop games for Playdate.”

Panic originally planned to include twelve games in Season One, but have now doubled it, to twenty-four!

“There’s just so many amazing and different types of games that we had funded that it was just hard to not include,” says Arisa Sudangnoi, who handles Developer Relations for Playdate.

“There’s some people that were just already part of the Playdate community that we ended up including in Season One. And one of the developers, Nick Magnier, had been in the early developer community, I guess, for Playdate. And so seeing his game in the community, we thought that the game was a pretty good fit.”

Greg was thrilled to bring Arisa onto the Playdate team.

“Arisa came to us from Valve and she is our Developer Relations manager, meaning that she is in charge of communicating with all of our game developers about Playdate—what’s going on with us and finding out from our developers what they’re working on, what issues they’re having. And that’s key for a product like Playdate, because the 24 games that make up the season are really a huge part of the value of Playdate. And so we want to make sure those games are, are top notch and it’s a Arisa’s job to make sure that developers know what we’re doing and they’re informed about our schedule. So she’s on top of all that. And then also she’s taken on a bunch of other duties, like working on our warranty and our return policy. And it’s just been a huge help. She’s done a great job.”

“Everyone seems pretty easy to communicate with,” says Arisa. “It’s pretty awesome that we have just people around the world from the US to Japan…Germany. I think the main thing was that we want to make sure that we’re not just having developers that are already established, just having, you know, developers from all sorts of backgrounds that are interested in making games for the Playdate.”

So, how did Panic find the developers whose games will be included in Season One?

“We obviously knew there’s no way we’re going to be able to build all the games for this thing by ourselves,” says Cabel. “And so the first question we asked was, ‘who do we know that can make games?’ And fortunately our paths have crossed with many gamers over the years of Panic.”

Fun fact: One of the weirder Panic overlaps was that we made t-shirts for the game Katamari Damacy. Years later, that connection led directly to its creator, Keita Takahashi, creating the game ‘Crankin’s Time Travel Adventure’ for Playdate Season One.

“I think I remember us all sitting down and just writing on note cards, the names of basically every developer that we thought was doing cool work, or we thought could do cool work and, it was a lot of note cards,” says Cabel. “It was a difficult process, because then you have to approach them and be like, ‘Hey, here’s this thing from—it’s hardware, from a company that’s never made hardware before, with a season system that’s never been attempted before, and a crank that’s never existed before. And our budgets aren’t super massive. Do you want to make a game for a device?’ Fortunately the cool thing about creative people and game developers is that, there’s definitely a group of people that just super resonated with that batch of ideas. One of the mistakes we made in marketing was leading with the big names and setting this impression that, like, here’s another device for that same club of indie developers that are successful, and that you’ve heard of, which is really not what we wanted at all. But, you know, marketing brain says, ‘oh man, you gotta get people excited about this thing.’ And you know, we got to use the big names and I think that set the wrong impression. And so we worked to correct that. That, like, early announcement really was beneficial for us, because it let us learn a lot of things, without selling the product yet. And it gave us an opportunity to correct a lot of things without selling the product yet. And I’m really, really, really grateful that we did that. So that allowed us to sit down and say, ‘Okay, the whole goal of this thing is that it’s for everybody. That you can get the development kit without having to pay a bunch of money, that every unit is a dev unit, that you don’t have to have special hardware to make a game for Playdate.’ We’re clearly trying to build something that is open and accessible, but the season needs to reflect that, too. We can’t have a season that says, this is for you the folks you’ve heard of, but also say this is for everybody.”

“And that was one of those times where, I mean—criticism. Nobody likes it, because it doesn’t feel good, but it comes from an important place and you have to listen to it because there’s a reason why people are saying, ‘Hey, this thing is, is… this doesn’t make me feel great.’ You can react to that in two ways. You can say, ‘well, too bad,’ or you can step back and say, ‘Oh, huh. Yeah, that’s right. I didn’t really think about that, and we will work on that.’ So we definitely took a step back and shored that up and reached out to more people and more developers and I think made the product and the season significantly better as a result.”

“It’s been kind of like my personal goal to bring in more voices to the game industry and more diverse voices,” says Arisa. “And so working with Sweet Baby, having that opportunity to work with them, has been really rewarding. They believe it’s very important that we provide a way for people to get work on a project and get credited for it so that they can put it on their resume and find other work in the industry.”

“Sweet Baby’s an incredible group of super-talented game makers,” says Cabel. “And we talked to them about making a game for Playdate, and they did. And then we talked about making more games for Playdate, because they have this incredible endeavor where they are connecting veteran developers with super talented developers that maybe don’t have credits yet, that don’t have the experience in a shipped game, but have incredible abilities and skills. And, like, that is such a hard barrier and you just, you need to be seen and you need to be taken seriously. And that’s really hard to do when you can’t say, ‘I shipped this.’ And so Sweet Baby’s awesome idea is to pair people up and have a combination of experience and new experiences. It’s so smart. It’s so cool. And so when they said, ‘Yeah, we would love to put some teams together to make even more games for Playdate,’ it was just a super no-brainer. I’m so glad to be working with them. And the stuff they put together is super inspirational for us. It makes us excited about the platform. Again, it’s just that great feedback loop of, like, happiness, which is the best case scenario for a collaboration.”

Sweet Baby’s “Lost Your Marbles” is just one of twenty-four amazing games that will be included with Season One. You can see the full list of games on the Playdate website.

And outside of Season One, Panic also has an ongoing Playdate Developer Preview.

“The Playdate Developer Preview was a way for us to really accomplish two things,” explains Cabel. “One: get Playdate in the hands of brand-new developers who have not touched this platform before and see how it goes. What’s confusing? What was hard to set up? What do they need from our SDK? It’s just a fresh set of experiences. That in a way, it’s kind of like a beta test of the SDK and then simultaneously kind of a beta test of our hardware. This has allowed us to check, does anybody have any problems with the crank? You know, we’re going to manufacture a lot of these and send them out. So we really gotta make sure that they’re good.”

“And because we had a very limited number of units to give out, versus the amount of interest there was from developers, there are only two hundred to three hundred developers in the Preview right now,” adds Arisa. “We plan on expanding and releasing the SDK publicly at some point in the future, but we’re wanting to kind of make sure that we can provide the sort of support that developers need and the documentation necessary before we do so.”

“The Developer Preview kind of solved both birds with one stone. You don’t solve a bird with a stone! I just don’t want to talk about killing birds,” laughs Cabel. “Yeah, it was a twofer. It was actually tremendously useful, and the best part about the Developer Preview for me was watching people go from zero to, like, something in a really short period of time, which told me that we are kind of on the right track.”

There are tons of developers who have been making really cool stuff. So: what about a Season Two?

“If we do a Season Two,” says Cabel, “we will have that audience that already has Playdates sitting on their desk. So the dream of a synchronized season is way more possible with a Season Two, than Season One. So, you know, we’ll see how that goes and cross our fingers that that can exist.”

“Who knows what might happen in the future?” Says Steven.

Regardless, it’s truly amazing to see the ingenuity and variety of games that people have been creating for this tiny device with a one-bit, black-and-white screen.