Panic Blog

Nova is Here.

By Cabel

A quick belated announcement: after years in development, Nova, our next-generation, fully native, future-focused code editor — only available for macOS — is here.

The Future

Rewritten from the ground up, Nova is lighter, faster, more flexible, and deeply feature-packed. It has a modern, hyper-speed editor with all the features you’d expect. It has a customizable user interface. It has a robust extensions ecosystem. It can work on local projects, or work directly off your server. It has tools like a Terminal and Transmit-based File Browser. It’s designed from the ground up to enable complex web workflows that might have build, run, and deployment phases… but it’s still great for a good old static site.

I could go on all day, but you should just check out the website, and try the free 30-day demo.

Own It Forever

Nova is $99. And when you buy it, you own it — it will never expire. It also includes one free year of updates — including new features and fixes — which we’ll release the moment they’re ready. Also, if you want, you can get additional years of updates for only $49 a year. But that’s totally optional, and there’s also no penalty to signing up for updates later, either when you’re ready, or when we’ve added a new feature you want.

Just The Beginning

We have big plans for Nova. We are, as they say, just getting started.

If you have any questions, first check the Panic Library, which is an invaluable resource. Then, feel free to drop us a line.

We hope you enjoy it. And welcome to the future!

Saving Face

By Michael

Episode 4 of the Panic Podcast, Audion & On, hit the podcast feeds last week, but if you play the episode directly from our podcast page using the “Play Now” button, you’ll find a nice surprise waiting for you.

We wanted to give our listeners an opportunity to experience some of Audion’s amazing faces for themselves. No matter how well we described them on the podcast, we couldn’t do them justice. The faces aren’t just visual: they’re interactive.

They’re also an important part of Panic’s history that has been inaccessible to modern computing devices for well over a decade. Although they were cutting-edge technology when Audion launched 21 years ago, porting them to modern Web browsers was an involved process. In this post I’d like to give you a peek at how these faces work, and touch on what it took to bring them to the Web.

Painting a Picture

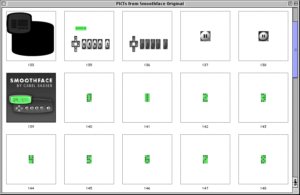

At their core, Audion faces consist of a base image, with smaller images drawn over it. The base image contains not only the background of the face, but all the buttons and UI indicators.

Buttons in Audion can have different appearances when they’re pressed, when they’re disabled, and when the mouse pointer is hovering over them. Each of these appearances has its own image.

For each frame of animation, the base face is drawn first and any special appearances for the buttons are drawn over that.

The other UI elements—the UI indicators, the play time, the track number, and the various animation frames—are then drawn over the face. Faces can display animations when connecting to a stream, when playing a stream, and when the stream is lagging. Face designers can use as many frames as they’d like for these animations, and they control the speed of the animations. Because of this flexibility, each animation frame is stored as its own image.

Drawing images this way is not difficult to do in modern Web browsers. However, the faces themselves used Classic Mac OS file formats which are not well-supported today.

In the Old Days

Audion started as a Classic Mac OS application, and, like most Mac OS applications at the time, it used resource forks to store its assets. Resource forks are a Macintosh-only technology designed to store metadata associated with a file. Every file in Classic Mac OS has a data fork and a resource fork. For Applications, the data fork contains the machine code that was run, and the resource fork contains the icons, graphics, sound, and text strings used by the application. This allowed Mac applications to be distributed as a single file, while Windows applications are typically comprised of multiple files.

A year after Audion launched, Apple released the first public beta of Mac OS X. Although it still supported resource forks, Apple began to discourage their use. In their place, Apple promoted the use of packages. Packages are special folders that appear to be a single file on macOS, but look like normal folders on other systems. They serve many of the same purposes as resource forks, and many users wouldn’t notice any difference between the two technologies. More savvy users, however, began to see resource forks as an artifact of old, outdated software, putting pressure on developers to move to Apple’s newer technologies.

In 2003, Panic alumnus Les Pozdena worked on an app to convert Audion faces from resource forks to a package-based format. Audion was discontinued soon after, so these package-based faces were never used, but the face converter code remained in Panic’s source code archive. When Christa first mentioned that she was doing a podcast about Audion, the idea of adding Audion faces to the podcast page immediately popped into my mind. At the time, I had no idea how the faces worked, and Les’s code provided an invaluable starting point.

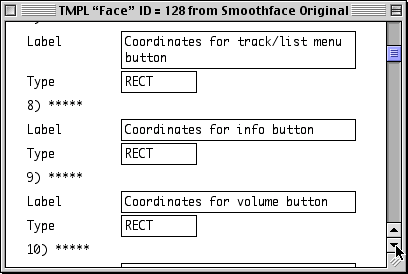

Updating the Converter

Les’s converter was mostly complete. It could already open resource files, extract images and their coordinates, and convert images from the PICT image format to PNG, an image format in wide use today. However, the code needed to be updated to run on modern versions of macOS. It used a few functions which have been removed from macOS since the converter was written. The converter also didn’t support UI indicators. Many newer faces, like Smoothface 2, don’t have these indicators. Thankfully, the face files themselves provided a description of their format, making it easy to fill in the missing details.

After a few hours of work, I set the converter loose on the files in our Audion face archive. After I finished, I noticed that some of the faces were using the wrong text color for the artist and album text fields. As it turned out, these fields could optionally be styled by a separate text style resource. This resource contained the text’s color, its styles, (e.g. bold, italic) and its transfer modes. None of the faces on the podcast page use special transfer modes, but if you’re interested in learning about them, they are documented in Inside Macintosh: Imaging With QuickDraw.

Converting the faces for the Web required making a few changes to how they worked. When drawing to HTML’s <canvas> element, you can get better performance by redrawing as little as possible. Audion redrew the face every frame starting from the base image because it needed to in order to get transparency right, but that’s not required on modern computers. The converter therefore cut the button and indicators out of the base image. This allows the base and the buttons to be drawn separately.

The most challenging part of displaying the faces on the Web is text rendering. There are two reasons for this. The first is that many Classic Mac OS fonts contain a set of bitmap glyphs that were used when drawing the font on screen and a separate set of outline glyphs used when printing. The bitmap glyphs were designed to look good on low-resolution screens and were faster to draw than the outline glyphs. Modern operating systems exclusively use the outline glyphs, which makes the text look quite different. This was noticeable back in 2001. Audion’s text looked different in Mac OS X than it did in Classic Mac OS. However, HTML’s <canvas> element offers very little control over text rendering, and each Web browser draws the text differently. If you used Audion back in the day, the text on the page will not look exactly like you remember.

The second problem is that many Audion faces used custom fonts, and some of these fonts have been difficult to convert for the Web. Mac Postscript fonts also stored their font data in resource forks, and although there are many tools to convert these fonts to other formats, these tools fail to convert some of these fonts correctly. It is likely that we will need to write a bespoke tool to convert these fonts. The faces in our archive use a total of 95 unique fonts, and converting them all will take some time.

Hidden Details

Not every image in the face is used in the Web player. For example, we couldn’t find a good use for the inactive face image, which is used when Audion was in the background. The drag region, a bitmask image which Audion 1 used to draw face outlines while dragging, was the most interesting of these images.

Some face designers used this image to sign their work.

Others used the drag region to hide messages or drawings.

When SoundJam first added support for Audion faces, they incorrectly used the drag mask for transparency, causing these messages to be cut out from the face. Because of this, some face designers would hide advertisements for Audion in the drag region.

Preserving Audion for the Future

It’s wonderful to be able to show off these faces on our podcast page, but it’s also important to preserve them for the future. A few of the faces in our archive are offensive, especially in a modern context, but they may be useful to future historians.

However, as time goes by, it will become harder to preserve these faces. The face converter already does not currently work on macOS Catalina because Catalina removed support for working with resource forks and PICT images. There are third-party libraries which can read these formats, but much more work would need to be done to the converter to get it running in current and future versions of macOS.

That makes now the ideal time to convert and archive Audion faces. If you have any faces that aren’t in our archive, please get in touch so we can convert as many faces as possible.

For Fun

The most rewarding part of this process has been revisiting the many great Audion faces in our archive. There are good reasons we don’t design customizable software interfaces anymore, but they’ll always hold a special place in my heart. They weren’t just fun, they made personal computing personal.

If you’ve read this far, there’s a good chance that you also have a fondness for Audion. I hope you enjoyed this look into how the faces worked. I plan to post a followup in a few months detailing my progress converting the rest of the faces and showing off some cool finds.

Please look forward to it!

Nova. Our next big thing.

By Cabel

Hello, long-time Panic friends. It’s nice to see you again. We have a few quick — and important — announcements for you.

A new Mac editor.

You’ve been waiting. For a very long time. Us too. And we’re so happy to announce that the next Coda is almost here.

And it’s called Nova.

Our next great Mac-native text editor, Nova, is about to enter private beta. We’re looking for testers, and we’d love for you to be a part of it. We’ll be doing tests in groups, so the more we know about your editor usage, the better!

A few possible answers to a few possible questions:

Why “Nova”?

Nova is a dramatic upgrade in every respect, a total re-write and reimagining. It felt appropriate to give it a new identity.

Is today’s Coda dead, then?

Nova is replacing Coda, but if you like using Coda there’s good news: we’re planning a final Coda update soon to add support for macOS Catalina, and we will always update Coda if any major security issues are discovered. Importantly, if you like how Coda works and haven’t yet purchased it, do that now — it will not be for sale in 2020.

How much will Nova cost?

We’re still figuring this out. We’re leaning towards a Sketch-like “buy it, keep it forever, and get a year of feature updates” model. We also hope to provide a discount to Coda 2 owners, to be determined.

Will Nova be in the Mac App Store?

Not at this time. This is because of Nova’s heavy reliance on arbitrary third-party executables and extensions, prevented by sandboxing.

And later, an updated iOS editor.

We’ve also begun work on a new version of our iOS editor. It won’t ship at the same time as Nova, and it won’t be a feature-complete copy of Nova for Mac — rather, we’re planning something that hopefully strikes an ideal balance between Nova-like functionality, and Transmit-like functionality, for on-the-go work.

But! Until this new version is ready, we’ve somewhat-comically renamed the current app to just “Code Editor“, since there’s a new Coda in town — a reimagined document at coda.io. So, don’t be alarmed if you search for Coda for iOS and wind up with Code Editor. That’s us!

We can’t wait to get these new apps in your hands!

After more than 20 years of making quality apps you love for Mac and iOS, Panic was ready to try something new…

…and that something was hardware.

Today, after more than four years of work by a small and talented team within Panic, we are extremely excited to introduce Playdate, a brand new handheld gaming system, arriving in early 2020.

Playdate is both very familiar, and totally new. It’s yellow, and fits perfectly in a pocket. It has a black-and-white screen with high reflectivity, a crystal-clear image, and no backlight. And of course, it has Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, USB-C, and a headphone jack. But it also has a crank. Yes, a crank: a cute, rotating analog controller that flips out from the side. It’s literally revolutionary.

It also includes a full season of original games, at no extra charge, delivered each week to the system — games in all sorts of genres that are all hopefully surprises.

Yes, this is all real.

Now before you ask, and you will ask, don’t worry, yes we’re still developing Mac and iOS software. In fact, we’ll be releasing a preview of the next major version of Coda later this year. Stay tuned!

But if you enjoy games, if you like beautiful things, or if you just enjoy having fun, you might enjoy Playdate. Hopefully it’s unexpected, but also totally Panic. We really think it’ll brighten your life.

Hello! Panic has an opening for a Web Services Engineer to join our award-winning team at our Portland, OR headquarters.

We’re looking for a Python developer with Django experience to help us maintain some of our existing web services and write some new ones!

We don’t currently support remote work, and would prefer to hire someone already in the Portland area, but we still encourage anyone to apply and would relocate someone within the USA if we can’t find a suitable local candidate. Please follow the link below to the job listing to see the other requirements for this position!

Now, it’s possible you might not think of Panic as much of a “web services” place. I get it. But there’s actually a lot going on over here! in addition to our rock-solid Panic Sync service, and our homegrown eCommerce platform (“Circle”, which just underwent a massive modernization rewrite), we have upcoming services needed for the next major update to Coda, as well as other very cool undisclosed future projects.

You’ll call a lot of shots, you’ll own a lot of things, and with any luck, it will feel pretty good. Sound interesting?

Head on over to our jobs page and submit your resume soon.

Also, there’s one other thing I want to mention again that’s not explicitly stated in the job posting: if you read our qualifications, feel like you’re really really close to matching them all but you’re missing one, or maybe you aren’t a super confident person or feel a touch of the ol’ imposter syndrome creep in as you read the page, please consider pushing through and applying anyway. None of us here are perfect geniuses or have it together 100% — we’re all just doing the best job we can, and I’m confident you can do that too.

We really look forward to hearing from you.